HGBW #3: Pride and Prejudice and Story Structure

Starting this week, we’re taking a deep dive into the writing choices and techniques that make Pride and Prejudice a great novel. (If you haven’t read it already, check out this post on how Jane Austen makes her characters lively through density of action). Let’s start by asking, what kind of story is Pride and Prejudice? And, what elements do you need to write that kind of story?

The Elements of Romance

The answer to the first question is straightforward: Pride and Prejudice is a romance. We know this because its central dramatic question is, “Whom will Lizzie Bennet marry?” Many stories contain a romance subplot, but in a true romance, the protagonist’s search for a relationship drives the action and the protagonist’s growth as a character.

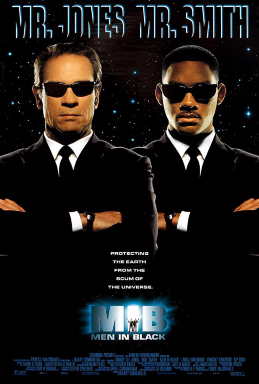

In a romance, the protagonist begins with a flaw and needs to overcome it to end up with the right person. Usually, the suitor needs to grow and change, too. Film romances typically foreground one suitor and show us how the protagonist comes together with that person. The relationship prompts both people to develop until they become better versions of themselves—versions that are suited to be with their partner. There’s conflict and give-and-take as each partner comes to understand the other. This is why, in terms of story structure, a rom-com is almost identical to a buddy-cop movie. Both tell stories of two people who seem poorly matched but discover that each has something the other needs.

Romance is the structure of many great novels, including Anna Karenina, Portrait of a Lady, The Tale of Genji, and Middlemarch. It also flourishes in film, TV, and popular fiction. Certain elements occur in nearly every romance, from The Divine Comedy to The 40-Year-Old Virgin. Here are some of the main elements that we need:

- A protagonist.

- The protagonist’s flaw. A good way of identifying the protagonist’s flaw is to ask, “What habit or characteristic is preventing our hero from being with the love interest?”

- The protagonist’s world and its rules. This includes the protagonist’s social order (e.g. Regency England, with its gender roles) as well as the characters in her community, work, family, and other parts of life. To some degree, she has been able to make her way in this world. The world has certain rules, and she is able to follow them and get by. In other words, her world has allowed her to get away with her flaw.

- An instability in her world. Something needs to push the protagonist out of the life she is living when the story begins. The instability can be internal (she’s unhappy) or it can be external (she loses a job she thought she loved). But something needs to drive her to step, irrevocably, beyond her boundaries.

- Suitors. In a romance, the protagonist’s interactions with suitors drive the action forward. Suitors offer different lives that the protagonist could live. They represent possibilities.

Now, how do these elements work in Pride and Prejudice?

The Protagonist

Lizzie Bennet. Lizzie is smart, capable, observant, and funny. She has a keen read on the people around her. She is kind and goodhearted, sometimes dramatically so (she walks three miles through the mud after a storm to take care of her sister while everyone else worries about getting dirt on their clothes). Her mother and younger sisters irritate her, but if someone outside her family judges them, she leaps to her family’s defense. And because she is so clever, she does not suffer fools lightly.

The Protagonist’s Flaw

As for many people, Lizzie’s faults are the flip side of her strengths. She is smart and strong-willed, so she makes snap judgments. She believes her judgments to be sound because, often, they are sound. Her keen powers of observation lead her to understand people quickly…and to judge them equally quickly. Eventually we see that Lizzie’s assessment of people is not as reliable as it first seemed. Sometimes, she wildly misjudges people. She needs to learn to look deeper, to see that things are not always as they seem.

The Protagonist’s World and Rules

Lizzie lives with her family, and each member has a clearly defined role. Lizzie adores her father, who is witty and affectionate toward her but sarcastic toward his wife. Her older sister Jane is warm, kind, and loving. Her youngest two sisters are young, silly, and boy-crazy, and her mother is obsessed with marrying off the girls. In this world, Lizzie’s mother will try to marry off the girls; the younger girls will go along with it. Lizzie will sit with her father making fun of it all. Nice work if you can get it.

Of course, Lizzie’s world also includes the expectations of Regency England. Her world offers no jobs to middle-class women; the girls must marry or face a life of poverty. In this world, a “good” match is one in which the husband is financially secure and socially prominent.

The instability

Lizzie’s father’s inheritance is entailed, so when he dies his house and all his money will pass to a male cousin. Lizzie enjoys life with her family and she is reasonably happy, but a time will come (no one knows when) when the women will be forced out of their home. If she wants a stable life, she will need to marry.

Suitors are Symbols

Let’s think in terms of story structure about how a suitor functions in a romance. We’ve already seen that suitors drive the action forward. By pushing the protagonist, a suitor catalyzes the protagonist’s growth. But they do something else, too. They are symbols.

A suitor represents a specific way in which the protagonist might to grow, as well as representing a vision of fulness or happiness. The nature of character growth determines what story we’re reading: Lizzie Bennet learns not to judge people so quickly, while Pam Beasley in The Office learns to stand up for herself.

Here’s the difference between a classic novel like Pride and Prejudice and a great film romance. A film usually focuses on the relationship between the protagonist and one suitor. Sometimes there is a second, “wrong” suitor (often the protagonist’s current partner), but that character usually has a minor role because a two-hour film rarely has time to depict multiple suitors. With at most two suitors, a film generally stages a straightforward competition between two sets of values, one right and the other wrong.

But a novel can be more complex. In a great novel like Pride and Prejudice, several suitors compete for the protagonist’s hand and each one symbolizes a different set of values. The novel stages a conflict among several accounts of what it would mean for this person, the protagonist, to be happy. The protagonist flirts, literally, with different ways in which her life could go.

Next week, we’ll take a closer look at Lizzie’s suitors and their roles in the story. For now, here’s a question to think about: How many suitors does Lizzie have? The obvious answer is three. But from the point of view of story structure, she has four. We’ll talk about them next week,

Happy writing,

Bill

HGBW #3: Pride and Prejudice and Story Structure Read More »