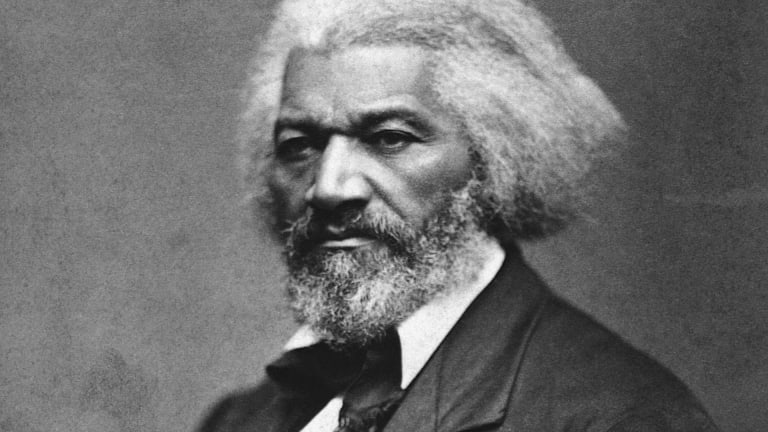

The simplest way to start a story is to introduce yourself. Your narrator states his name, tells us where he is from, when he was born, and describes his background. And yet, you can do so many things with a self-introduction. Here’s how Frederick Douglass, the great abolitionist author, begins his autobiography:

“I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvest-time, cherry-time, spring-time, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not allowed to make any inquiries of my master concerning it. He deemed all such inquiries on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a restless spirit. The nearest estimate I can give makes me now between twenty-seven and twenty-eight years of age. I come to this, from hearing my master say, some time during 1835, I was about seventeen years old.” (Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, 1845

Douglass’s Narrative tells us where he was born, but immediately runs into a problem: Douglass cannot tell us when he was born, because he was born enslaved. In 19th Century America, births had long since been recorded; there’s something unsettling about not knowing your birthday. It’s even more unsettling that he learns his best estimate of his age only because his owner told him.

Douglass wants to unsettle us. Many of his first readers were white northerners who disliked slavery but didn’t know much about it. He aims to show them what slavery is really like. He doesn’t start with beatings or torture (he’ll get there soon enough), but with a hidden privation. Most free people would not even think about it. It is as if he says: there are terrible things about slavery that you know about. There are also terrible things that you have never heard of. I escaped from slavery to tell you, and I will be your guide.

Douglass establishes his credibility by surprising us. That is a key point for writers, whether of fiction or nonfiction: readers begin to trust us when they learn from us. A powerful way to earn trust is to show readers something that was right there in front of them—but which they did not see, and would not have seen, without the writer.

What’s more, this small-seeming observation—that enslaved people do not know their birthdays—makes the world of enslaved people alive for Douglass’s readers. He makes that world real and concrete by fixing on an overlooked difference between life in slavery and life outside of it.

Douglass’s ignorance of his age does one more thing: it introduces Douglass’s quest to understand himself and his world. A major conflict in this story occurs between Douglass, who wants to understand the world, and the slave owners who want to keep their slaves ignorant. Douglass relates his growing understanding of the sick logic of slavery, from the beating of his aunt to the slaveowners who encourage their slaves to drink so that they remain ignorant. Many of the book’s famous scenes revolve around Douglass’s attempts to learn. When Douglass is a child, his master’s wife tries to teach him to read, but her husband berates her for it. Later, he finally learns to read by tricking white sailors into teaching him. All throughout, he argues that slaveowners’ most powerful weapon is their ability to keep slaves ignorant about themselves and their condition, and that their best way of fighting back is to learn. Douglass doesn’t say any of this in the first paragraph, but his desire to know his birthday reverberates through the whole book.